Tutorial: How to plan a venture capital round?

Raising venture capital changes your cap table fast—often in ways that are hard to “feel” until you run the numbers. This tutorial walks you through realistic funding scenarios so you can understand dilution, valuation, and option pools before you negotiate.

What you’ll learn

- How pre‑money and post‑money valuation work, and why they matter.

- How issuing new shares dilutes founders and existing shareholders.

- How an option pool changes ownership on a fully diluted basis.

- How different term choices reshape the cap table across rounds.

Table of contents

Who this is for: founders, early employees, angels, and anyone preparing for a first (or second) equity round.

How we’ll do it: we’ll use fictional numbers and cap‑table simulations (via Simulfund) to visualize the results step by step.

Key definitions (quick)

Venture capital (VC) is a type of private equity financing used to support startups and early-stage companies with high growth potential, typically in exchange for equity (ownership).

Venture means taking risk; capital means long‑term resources (money, skills, and know‑how) used to build a company.

The risk is that a startup may fail due to execution, competition, regulation, technology shifts, or management mistakes—but the upside is that successful companies can grow quickly and deliver strong returns.

The core mechanics

Pre‑money valuation is the value of the company before the investor adds cash.

Post‑money valuation is the pre‑money valuation plus the new investment.

Pre‑money valuation = (shares outstanding) × (price per share).

Post‑money valuation = pre‑money valuation + investment amount.

Next, we’ll run Case 1 and Case 2 and compare how each offer changes the cap table for the founder, existing shareholders, and the investor.

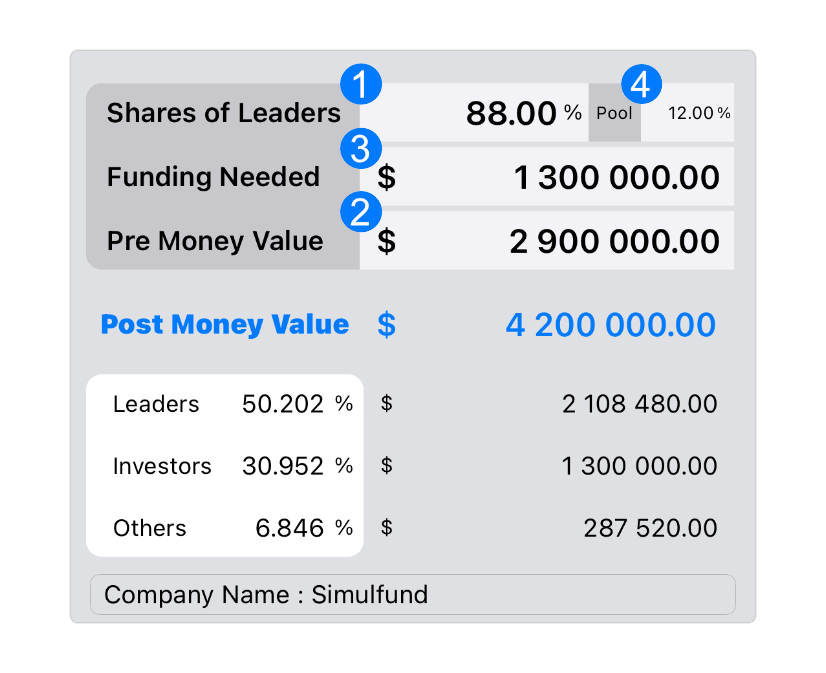

Case 1: Assume the founder proposes the following terms to a venture capital investor:

- The founder currently owns 88% of the company.

- The pre‑money valuation is $2,900,000.

- The funding needed is $1,300,000.

- The option pool is set at 12%.

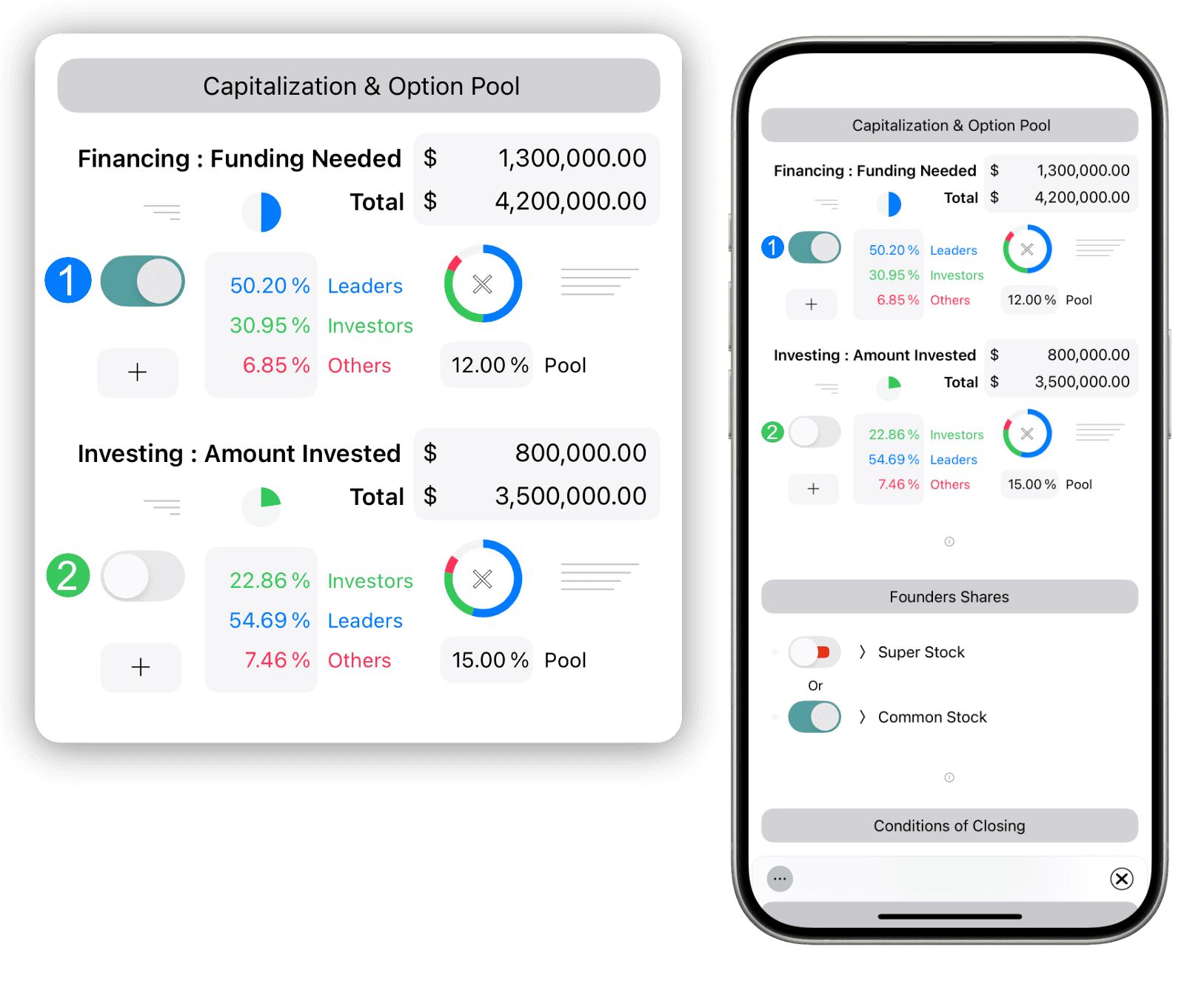

With these inputs, Simulfund computes a post‑money valuation of $4,200,000. After the round, the founder’s ownership drops to 50.2%, the other shareholders drop to 6.8% (down from 12%), and the investor receives 30.95% of the company for a $1,300,000 investment.

Now imagine the investor wants different economics—specifically, they propose investing less money than the company says it needs.

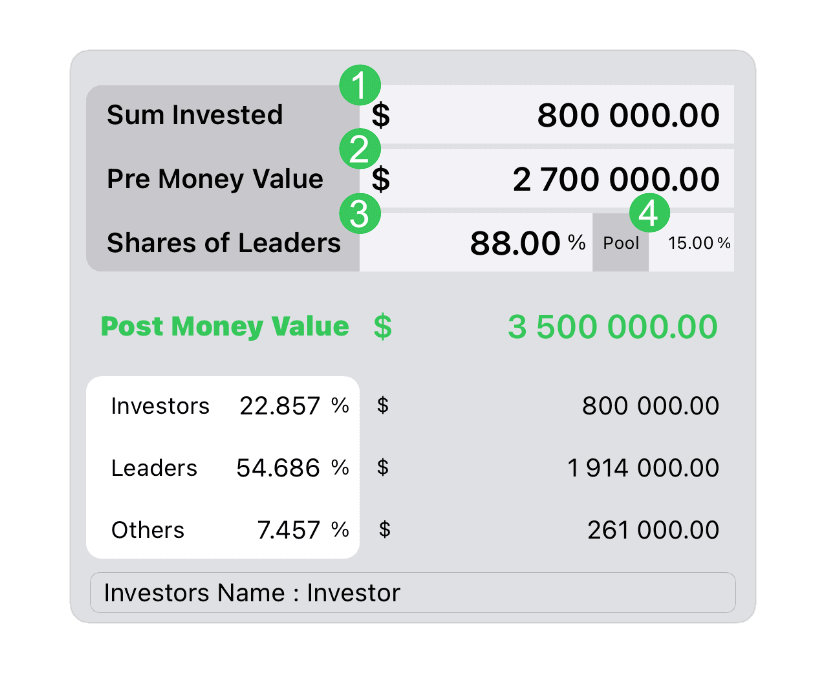

The investor proposes the following terms:

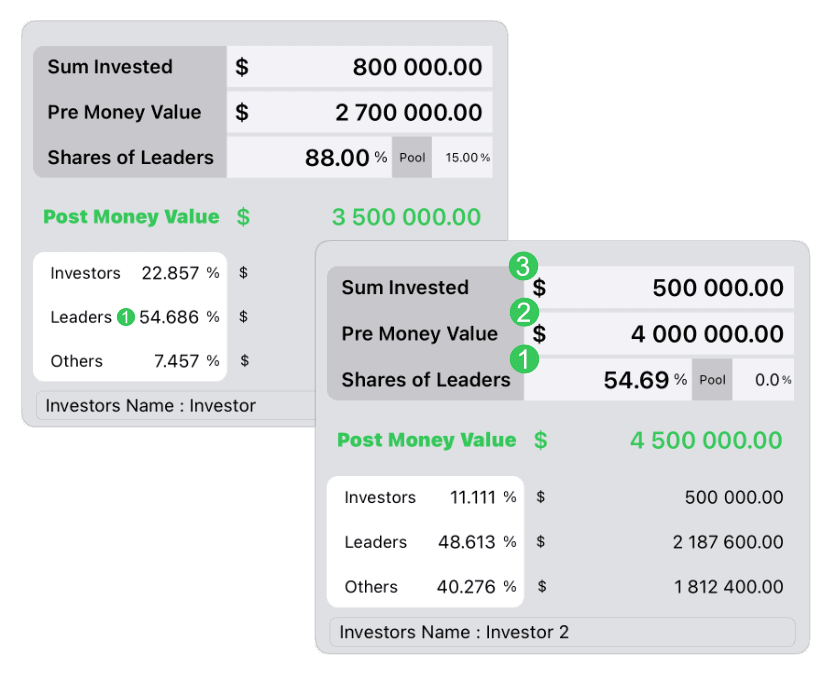

- The investment amount is $800,000.

- The pre‑money valuation is $2,700,000.

- The founder still owns 88% before the round.

- The option pool is increased to 15%.

On a fully diluted basis, you may notice that the founder’s percentage can look higher than in Case 1, but both the investment amount and the pre‑money valuation are lower. That typically implies a lower price per share (and therefore a lower valuation for the existing shares) compared to the first proposal.

Dilution from newly issued shares reduces the ownership percentage of existing shareholders, but it can still increase the value of what they own if valuation and pricing move favorably. In practice, the outcome depends mainly on the pre‑money valuation, the investment amount, and whether the option pool is included on a fully diluted basis.

Assume the parties accept the investor’s proposal in (2).

Before the deal, assume the company’s initial (nominal) valuation was $100,000. With the founder holding 88% of the shares, that stake corresponds to $88,000, while the other shareholders (“Others”) hold 12%, or $12,000.

Is this outcome good for current shareholders—and how can you evaluate it?

After the transaction, the “Others” shareholders are diluted to 7.46%, yet the value of their stake rises from $12,000 to $261,000—about 21.75× higher (a 2,075% increase). This shows how dilution can still coincide with value creation, but outcomes like this are hard to achieve in real venture capital deals and depend on many assumptions (pricing, terms, timing, and execution).

Finally, let’s compare the two simulations to see how each approach reshapes the cap table for every party.

(1) In the founder‑led proposal, the company’s pre‑money valuation is higher than what the investor is willing to accept for the new shares.

(2) In the investor‑led proposal, the option pool is larger and the investment amount is below the company’s stated “Funding Needed.”

To go one step further, we’ll now run a second funding simulation with a new investment to show how to structure—and manage—a follow‑on deal.

Case 2: Let’s continue the simulation. The company still needs an additional $500,000 to complete its funding target (“Funding Needed”): $800,000 + $500,000 = $1,300,000.

Now assume a new investor wants to invest on a fully diluted basis. This means the existing (but not yet issued) option pool is included when calculating ownership percentages.

With that assumption:

- The founder now owns 54.69%*.

- The pre‑money valuation is set at $4,000,000**.

- The investor invests $500,000.

* Previously it was 88%. If you ignored the option pool entirely, the founder would hold 67.89% rather than 54.69%.

** You may notice the new pre‑money valuation is higher than the prior post‑money valuation. In this example, we assume the company’s shares are now priced higher, largely due to progress and momentum created by the previous investment.

Scenario 2 is a good model for real fundraising: many startups raise capital in multiple rounds, from angels to venture capital investors. Each round can dilute existing shareholders, but if the company’s valuation grows between rounds, value creation can outweigh dilution.

In practice, professional investors usually propose “market” terms before committing capital. If you are leading a startup, it’s smart to prepare by running your own simulations so you can discuss trade‑offs with a clear baseline.

To go further, we need to look briefly at term sheets and a few common provisions—so you can understand what they mean, why investors ask for them, and how they affect your deal.

A term sheet is usually not intended to be legally binding overall, but it may include binding sections (commonly confidentiality, exclusivity, and expenses) depending on the document’s language.

Important: This tutorial is for general information only. If you plan to negotiate a term sheet, get advice from qualified counsel in the relevant jurisdiction.

Which venture capital terms do investors commonly use to protect their investment?

Investors can use many terms to reduce risk and keep the company on a path to growth. In the sections below, we’ll walk through scenarios to explain how specific provisions work—and why some investors may pause (or renegotiate) unless key terms are clarified.

If you are not experienced, remember that this tutorial is for general informational purposes only and may not be fully relevant to your specific situation.

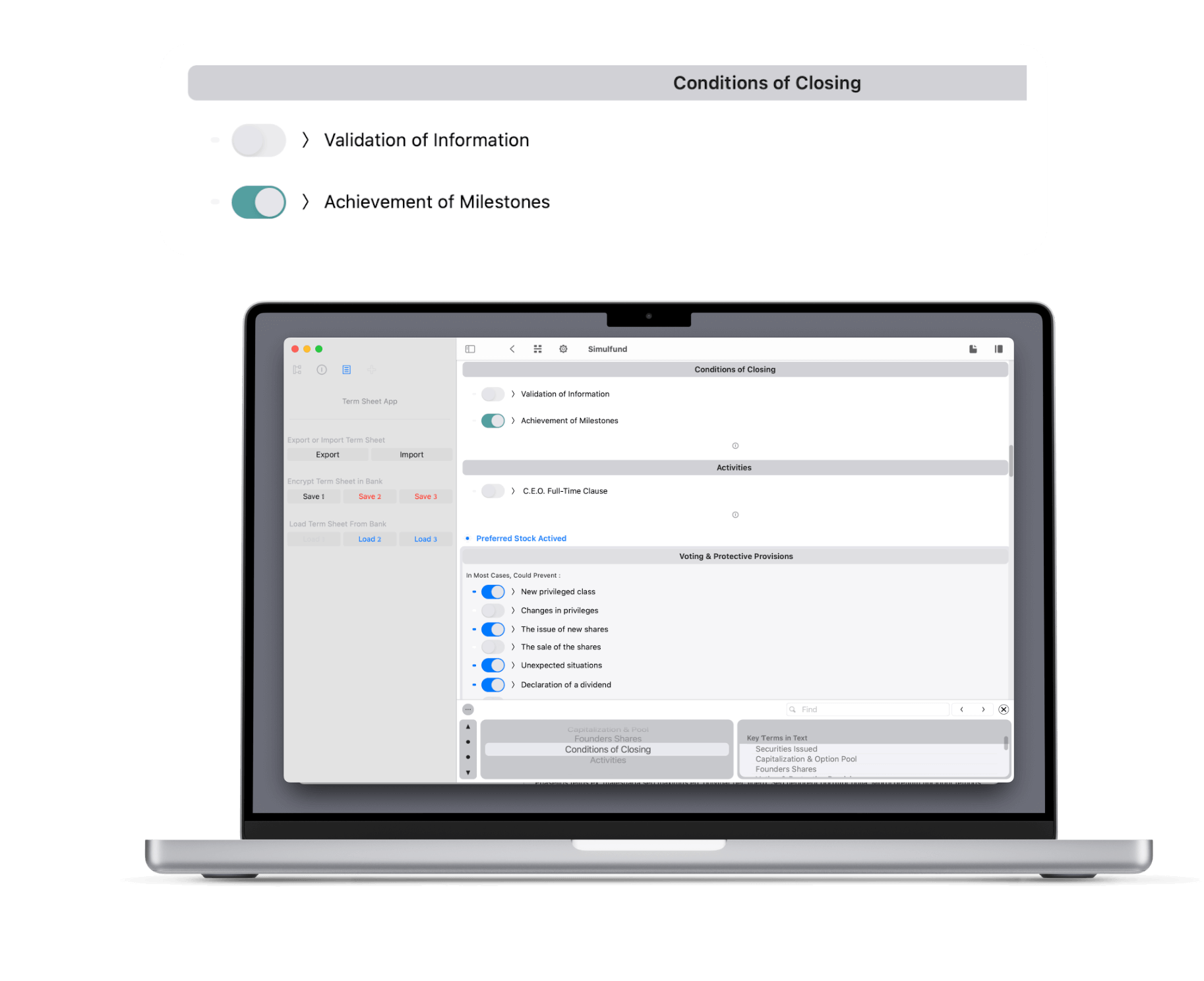

A. Milestones: How investors reduce risk with a roadmap

Setting clear goals—and hitting them—can strengthen trust between founders and investors and position the startup for future rounds. Rather than investing all the money upfront, an investor may include a milestone clause that releases capital in stages based on measurable results.

For a founder, this can be an opportunity to prove that capital is being converted into real progress. It can also align funding with execution and give both sides time to reassess.

And as we saw in Case 2, when a startup raises money across multiple rounds, dilution may increase over time—yet valuation can also rise, which can benefit existing shareholders if the company keeps creating value.

This is also why early investors often prefer to buy shares when the company is very young (or even before it is formally incorporated): uncertainty and lower valuations can translate into more upside if the company succeeds.

*The best investors don’t just “take risk”—they actively help founders execute by supporting hiring, product strategy, sales growth, and operations, while keeping incentives aligned.

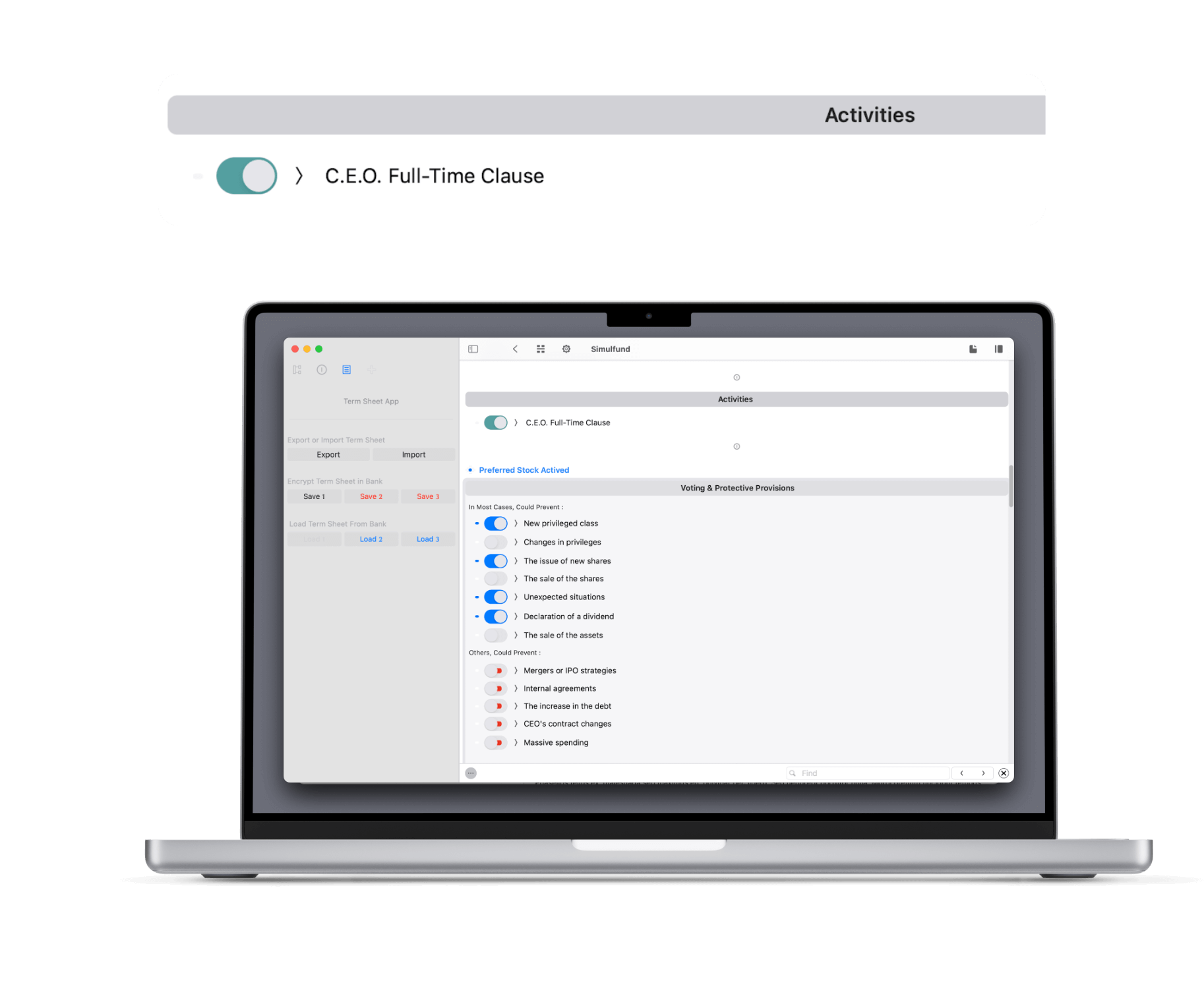

B. CEO time commitment: What if the leader is distracted?

Now consider the CEO’s day‑to‑day focus. After the deal is signed, the CEO may be pulled away by other ventures or responsibilities. If attention shifts, execution can slow down—creating risk for investors.

Depending on the context, investors may address this before investing by adding provisions that ensure adequate leadership focus and accountability.

Building a startup is hard even with sufficient funding. Creating value requires sustained attention and consistent execution—especially in the earliest phase. That’s why a part‑time CEO can be a serious concern in early-stage fundraising.

This is why investors sometimes request “key person” or time‑commitment clauses, to ensure the company has effective leadership to execute the plan.

Disclaimer: All information in this article is for general informational purposes only and does not constitute legal advice. Please review the terms of service that apply when using this website.